You are here: Home » New Outlook » Right Makes Rite

Right Makes Rite

by Lisa Kogen, Women’s League Director of Education and Programming

In a popular midrash, Moshe Rabbenu appears one day in the back of Rabbi Akiva’s classroom. Moshe asks a nearby student, “Who is that teacher, and what is he talking about?” The student responds: “It is Rabbi Akiva, teaching us the law of Moses.” Perplexed, Moses asks: “That is my law he is teaching?” The upshot, of course, is that the law had so changed over time that its chief architect could not recognize it.

So let us imagine a similar scenario. Solomon Schechter – the leading architect of Conservative Judaism who, in 1913, proposed a women’s auxiliary at United Synagogue – is seated in a January 2016 Women’s League Shabbat service. After witnessing women shlichot tzibbur, Torah readers and those honored with aliyot, might Schechter similarly ask: “Is this the women’s organization that I imagined?”

On reflection, Solomon Schechter would understand the Women’s League Shabbat service as a natural outcome of the organization he proposed that was established by his wife, Mathilde, just a few years later. First conceived to educate the flock of newly Americanized women who had barely rudimentary knowledge of Jewish ritual and learning, Women’s League can now proudly proclaim that mission accomplished.

In its earliest days, a small cadre of Judaically educated Women’s League leaders embarked on an ambitious mission, riding trains from coast to coast, visiting far-flung communities to teach members about Jewish history and kashrut and Bible and prayer. Contrary to popular mythology, most Jewish women knew little more than the bare basics about running a traditional household. Certainly an understanding of the textual foundations for those obser-vances and rituals was non-existent.

Another strategy of the early leaders was to publish instructive materials about Judaism. The most successful, The Three Pillars (1927) written by Deborah Melamed, was the first comprehensive guide for women in English, encapsulating the philosophy and ritual observances of Conservative Judaism. The Three Pillars, proof-read and approved by JTS Professor Louis Ginzberg, became an overnight success and eventually went through nine publications. It helped demystify Jewish ritual, making it accessible, understandable, and ultimately embraceable.

Throughout the decades, scores of other publications and resources furthered the founders’ mission. They included Shabbat study materials from the 1920s and ‘30s, The Jewish Home Beautiful of the 1940s, the Judaism- in-the-Home Project in the 1950s, the Celebration Series of the 1990s, the Hiddur Mitzvah Project (2012), and recordings of holiday songs and instruction-al CDs.

Sisterhood-sponsored udaica shops became another instructional tool for Women’s League. Seder plates, kiddush cups, candlesticks, challah boards and covers, kippot, jewelry, books and records all served to encourage the celebration of holidays and rites of passage. Often, the ritual objects came with written instructions and descriptions of their use and historical basis. Women were urged to give gifts of Judaica for weddings and bar mitzvahs as a way of enhancing Jewish identity – both for the giver and the receiver. The possession of a beautifully crafted kiddush cup or Shabbat candlesticks could be the gateway to in-creased and meaningful ritual observance.

Barely a half century after Women’s League’s founding, a new generation of educated Conservative Jewish women would seek to apply their knowledge and commitment in more public spheres.

In the early part of the 20th century, a significant number of rabbis’ wives served in a variety of para-rabbinic capacities, not only helping their husbands at a time when Conservative Judaism was taking hold in North America, but also creating new possibilities for women’s participation in public life. Tehilla Lichtenstein, Ruth Waxman, Libby Klaperman, and Rose Goldstein, to name but a few, were important contributors to Jewish life. Often assuming roles far beyond traditional ones, these rabbinic wives became exemplars, stretching the limits of women’s capabilities in the mid 20th century.

There were also earlier notable women pioneers. In 1916, Henrietta Szold firmly but gently rejected a male colleague’s offer to recite Kaddish for her mother, responding: “The Kaddish means to me that the survivor publicly and markedly manifest his wishes and intention to assume the relations to the Jewish community which his parent had, and that so the chain of tradition remains unbroken from generation to generation, each adding its own link. You can do that for the generations of your family, I must do that for the generations of my family.”

In 1922, 12-year-old Judith Kaplan, daughter of Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, celebrated her bat mitzvah at a Shabbat morning service, the first such event in North America. Standing just below the bimah at her father’s synagogue in New York City, with the Torah scroll covered but in sight, Judith chanted the blessings and read a portion of the Torah in Hebrew and English from her personal chumash, shocking even the Kaplan relatives.

By the 1950s and ‘60s, b’not mitzvah were increasingly commonplace. Initially they took place on Friday night, with the girl chanting biblical texts often related to stories about women such as the Song of Deborah or the books of Esther and Ruth. In the early days, the blessings were recited by the girl’s father.

Even though the Rabbinical Assembly approved aliyot for women in 1955 and then the counting of women in the minyan in 1973, the Shabbat morning bat mitzvah with the weekly readings only gradually be-came popular. Despite the great disparity in practice from synagogue to synagogue, Women’s League did not hesitate to advocate for and encourage greater female participation in all areas of public ritual.

In 1972, after Ezrat Nashim – the pioneering women who forcefully sought complete religious parity – was rebuffed by the Rabbinical Assembly from attending its convention, Women’s League invited the group to present their platform at its biennial. For the first time, at this convention, Women’s League members led their own services and Torah reading.

Almost a decade later, Women’s League showed its support for the ordination of women rabbis by passing a resolution at its 1980 convention. Similar resolutions were passed at conventions in 1982 (on equality for women in synagogue ritual and leadership) and 1992 (support for women’s prayer groups at the Wall).

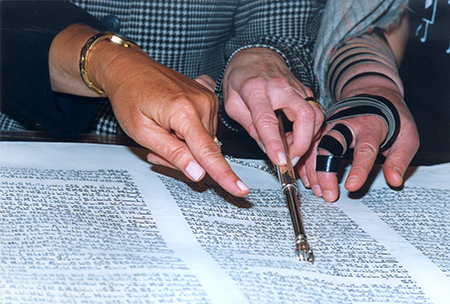

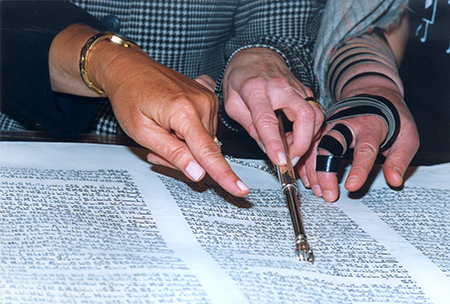

With the gradual inclusion of women in synagogue ritual, and as members acquired the requisite liturgical skills, Women’s League created Kolot Bik’dushah in 1993, an elite society of women who had mastered those skills. Kolot Bik’dushah has quintupled from its initial cadre of 250 women, recently inviting post-bat mitzvah girls to apply.

Today, all liturgical functions at Women’s League events are per-formed by members, as seen at hundreds of annual Women’s League/Sisterhood Shabbat celebrations. Just a few decades ago, members were permitted to read only English or non-prescribed Hebrew selections at a Women’s League Shabbat, with male members assigned the aliyot in sisterhood members’ names.

We cannot ignore another form of ritual observance introduced into contemporary Jewish life – celebrations born of feminist sensibility and creativity. These include rites of passage, holiday observances and events specific to women’s experiences. The past three decades have witnessed the popularization of baby naming ceremonies for girls, rosh chodesh groups, healing circles, and life cycle events marking widowhood, divorce and recovery from illness or trauma. Women’s seders and Vashti’s banquets introduce women’s experiences and voices into holiday celebrations. Kippot and tallitot, once exclusive-ly for men, have been embraced and aestheticized by women in a wide array of styles and designs.

Women’s participation in public ritual has changed forever the focus of Jewish life. Not only does it increase the potential number of Jews with both the skills and willingness to participate, it has also enhanced levels of creativity and energy. This is not change merely for its own sake, but change for qualitative improvement.

Members of Women’s League have fought long and hard for a role in public ritual with an ardent and impressive cadre of champions – women undaunted by the age-old admonition “but we always did it that way.”

Now we do it this way. And I fervently believe that Solomon Schechter would approve.