You are here: Home » New Outlook » Features » Diversity and Inclusion: More than Mere Buzzwords

Diversity and Inclusion: More than Mere Buzzwords

by Jane Calem Rosen

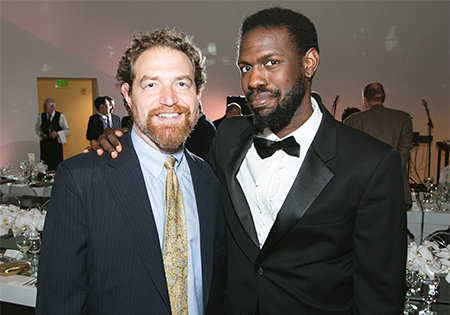

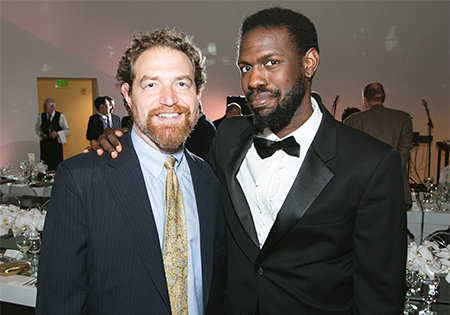

Rabbi Mike Rothbaum (left) and his husband, Yiddish singer Anthony Russell

On Shabbat, Chaim Respes, a 38-year-old human resources manager active in his New Jersey synagogue, dons a kippah and drapes a tallit over his shoulders. He enjoys attending services with his wife, a Jew-by-choice, and their three young boys. As one of the instructors in the congregation’s religious school and the recently ‘retired’ volunteer director of its youth programs, Chaim is a familiar presence, his picture visible on flyers in the lobby.

Yet, on more than one occasion, he’s been handed a tray during Kiddush or asked to set up the room, the assumption being that he is “one of the help.”

As a strapping African American male (6’ 4”), Chaim unwittingly feeds the perception that he is not ‘Jewish like us.’ It’s a perspective perhaps understandable, if not forgivable, in a society of “white privilege,” as Rabbi Menachem Creditor, spiritual leader of Berkeley’s Congregation Netivot Shalom, calls it. Rabbi Creditor addressed the issue in a recent Facebook post in response to a similar incident in his shul. A black woman, a long-time active member and Shabbat regular, had been asked if she was part of the catering staff, and was complimented for the day’s chair arrangement.

Being present, listening and calling public attention to the tacit, pervasive and often misunderstood hidden biases created by white privilege in synagogues and in society at large, Rabbi Creditor suggested, is the way forward for Jewish leaders. He hopes to spotlight the unwarranted and hurtful effects of white privilege. “I have no idea what it is to be black. I have no idea what it is to be anyone other than me. In the end, white privilege poses real challenges to everyone. White people have to listen and learn. The first step in addressing what white privilege creates is humility.”

“Just be humble, stay awake and show up,” he says.

Avi Rosenblum, now a soldier in the Israel Defense Forces

In a number of conversations we had about the experience of being black or bi-racial and Jewish in the era of Black Lives Matter, we heard a disturbing refrain. More than concerns over personal safety, which are real; more than the struggle with maintaining a strong Jewish identity while nurturing ties to one’s black or multi-ethnic/racial heritage, challenging as that can be; more than random, threatening run-ins with law enforcement, though not uncommon; many articulated the pain and trauma of alienation from places they consider home and from people that should treat them as family.

These are Jews by birth, some going back several generations within the United States, whose families had migrated from traditionally Sephardic, Caribbean or Latin American countries. (Chaim Respes’ grandfather, Abel Respes, for example, was born in Philadelphia, and his father was born in Georgia, with possible connections to slavery. Abel was the founding rabbi of Adat Beyt Moshe, a largely African American congregation that began in Philadelphia and later moved to Elwood, NJ.) Others are converts to Judaism, either by choice or as a result of adoption by Caucasian Jewish parents. They span the spectrum of age and Jewish observance, but all we spoke with had formal ties to the Conservative movement. “These Jews are not strangers,” one white Jewish professional said of his husband, black Yiddish singer Anthony Russell, a Jew-by-choice. “They are us; we are them.”

“’How are you Jewish?’ is an intensely personal question, and white Jews should not be making assumptions regarding Jews of color,” continued Rabbi Mike Rothbaum, co-chair of the Bay Area chapter of Bend the Arc: A Jewish Partnership for Justice, who at one time served as High Holiday rabbi at Temple Beth Sholom in Park Ridge, NJ. People are not entitled to learn, he contended, whether someone is Jewish by birth or conversion. “There’s halachah not to embarrass converts. Rather, we should be asking what are we doing to include Jews of color on our professional staffs in camps and schools or to raise them to leadership positions on temple boards and committees. How are we training our communities to not make Jews of color feel uncomfortable in their own communities? I’m very willing to publicly raise these questions.”

Chaim Respes and his family

So is Jared Jackson. A biracial Jew of multi-ethnic heritage who belongs to Germantown Jewish Center in Northwest Philadelphia, Jackson directs Jews in All Hues (JIAH), an organization he created to enlighten and educate Jewish communities committed to creating a diverse, inclusive culture. “We want to eliminate questions and perceptions about person-al identities and see that we are met with the same level of dignity as the person asking would want to receive.”

Jackson regularly consults with synagogue leadership and grassroots membership about engaging in a process that respects differences of all sorts, including LGBT Jews and a rainbow of skin tones. “No single workshop will be a quick fix,” he insisted. “We aim to change paradigms of how people are treated. We are also trying to help those who want changes in their communities to look at their internal attitudes and create strategic diversity plans. There are some wonderful communities out there, but not everyone is on the same page about wanting diversity. We need people with shared goals who want to continue Judaism on a different plane. Without first paying attention to our own problems and fixing those, we won’t be as effective in doing tikkun olam, repairing other issues in the world. Undoing bias is a daily process that involves building relationships.”

Jackson’s personal early experience in synagogue life was traumatic. Attitudes were so racist in his South Jersey congregation, he recalled, from the rabbi on down, that his family dropped its membership after he attended only one year of Hebrew school. By the time his year-old son is old enough for formal Jewish education, Jackson hopes the landscape will be different, but he retains a healthy skepticism based on realities he still runs into when he enters some Jewish spaces.

“I have had people call the police and observed mothers running away as I come near the building. Occasionally people stare and others try to educate me about how to read a siddur or explain the Hebrew.”

Yet, others do describe positive experiences within their synagogues.

For one Bay Area couple, Netivot Shalom epitomized a warm, embracing community when they trans-racially adopted and converted their son, Avi, 23 years ago and raised him strongly engaged in Conservative Jewish life. “There are lots of families that look like us in our community,” said Rom Rosenblum. The Rosenblums attended Shabbat services weekly, and Avi developed an unshakeable feeling of belonging as an Ashkenazi Jew and a Zionist, said his father. Now, when congregants visit Israel, they look up Avi, who made aliyah in 2014 and is now in the army.

Rachel Weitzner, of Baltimore, is the mother of three girls, 5, 3 and 19 months, with her African American hus-band, Greg Terry, who was in the process of converting when the two met. A nurse, Greg was a BBYO advisor for 10 years, beginning as soon as his conversion was completed. The couple feels fortunate to have a truly diverse, welcomng Jewish community at Congregation Beth Am in downtown Baltimore, where Rachel works in development.

Shabbat-observant, the family bought a house with a 90-year-old mezuzah on the front door, within walking distance of the shul. Their oldest attends the area’s Solomon Schechter Day School and Jewish day camp. The neighborhood, historically Jewish, is now racially and socio-economically diverse, not far from where the unrest occurred surrounding the shooting death of Freddie Gray in the spring of 2015.

“The reason we came to Beth Am is that there are many African American members here; a lot are black Jews and there are a lot who have adopted children who are African American,” explained Rachel. “It was important to us for our children to under-stand there are other Jews who look like them.”

But, she noted, “Beth Am is unique in Baltimore Jewish history. Most local congregations migrated out to Baltimore County. But Beth Am was founded by people committed to staying in this neighborhood and being part of the community of people of all races. Diversity among the membership is almost an outshoot of that.”

Chaim Respes gives credit to his rabbi, Aaron Krupnick, and hazzan, Alisa Pomerantz-Boro, at Congregation Beth El, in Cherry Hill, NJ, who, he said, “have created an environment in which all kids should feel comfortable. They set a tone for inclusion and diversity as best they can.”

Mike Rothbaum and Anthony Russell at their wedding.

In the final analysis, what has kept and keeps black and biracial Jews grounded in their Jewish identities and connected to Jewish community, regardless of biases and alienation and the sometimes misguided attempts by congregants to be welcoming?

“We subscribe to the Jewish value that people are valued regardless of their race or religion,” said Rachel Weitzner.

Others pointed to messages embedded in Jewish law and tradition strongly communicated in their homes, promoting social justice and treating all human beings with dignity and respect. Not surprisingly, these same Jewish values are what fuel and strengthen their racial identities, steering their moral and ethical compasses and helping balance competing racial-religious claims on their time and attention.

Hopefully these values will set a positive course for the future in making diversity and inclusion in Jewish communities more reality than myth.

“Being Jewish is a process,” observed JIAH’s Jared Jackson. “But so is being human. We all have an expiration date, but it’s exciting to see people go through processes and observe the shifts. You don’t have to end life as it began, with negative biases, in order to preserve what you had as a child or to preserve parts of what you are.

“Celebrate the parts of yourself and of others,” Jackson urges. “There’s no need to exclude differences within and outside of yourself. Integration is more salad bowl than melting pot, within individuals, communities and the broader society.”

HOW MANY AMERICAN JEWS ARE JEWS OF COLOR?

Determining how many Jews of color there are in the United States, regardless of movement affiliation, is itself a challenge. According to the 2014 Pew Center Religious Landscape Study, only two percent of Americans who identify as Jewish are black, with another two percent of mixed race or ethnicity (but not Asian or Latino). On the other hand, 64 percent of American whites, 12 percent of blacks, and 4 percent of mixed race individuals claim no religious affiliation, but may well be people born Jewish, according to Jewish law, or have at least one Jewish parent.